“The uterus is the rite of passage that is common to all of us regardless of race, class, gender. It is a common

space, it is like water – water is water, blood is blood, the womb is the womb, birth is birth. You are born from

someone, you come from that passage.” – Zanele Muholi

Southern Guild is pleased to present visual activist Zanele Muholi’s self-titled, autobiographical

exhibition from 15 June to 17 August. Occupying the entire gallery, ZANELE MUHOLI features

several monumental bronze sculptures – the artist’s largest presentation of new sculpture to date – and

introduces new photography in the Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail the Dark Lioness) series. The

exhibition also encompasses video work as well as a dedicated space for programming and

educational outreach.

Over the past few years, Muholi’s media-focus has broadened to reclaim ownership of their story

beyond their prize-winning photography. With self-portraiture as its predominant mode, ZANELE

MUHOLI presents a personal reckoning with themes including sexual pleasure and freedom, inherited

taboos around female genitalia and biological processes, gender-based violence and the resultant

trauma, pain and loss, sexual rights and biomedical education.

Muholi calls for new rites of self-expression, sexuality, mothering and healing that usher in kinder

modes of survival in our contemporary world. The exhibition is in part a response to South Africa’s

ongoing femicide, the stigmatisation of LGBTQI+ communities and the proliferation of gender-based

violence, especially the ‘curative’ or ‘corrective’ rape of Black lesbians. Muholi’s own struggle with

uterine fibroids and reckoning with their Catholic upbringing also deeply inform the exhibition’s

emotive symbology.

A recurrent theme in the artist’s work, the gaze is interrogated in a lightbox installation of

photographs from an early series, Being (T)here, Amsterdam, displayed in the public-facing windows

of the gallery. These images document an intervention that Muholi undertook in Amsterdam’s Red

Light District during their Thami Mnyele Foundation Residency in 2009 and depict the artist as a sex

worker wearing ‘umutsha’ (an isiZulu beaded waistbelt) and a black satin corset, posing in a window.

The photographs capture spectators as they approach the red glow that frames a young, feminised

Muholi. Although their poses are powerful and alluring, there is a point at which they break away

from the voyeur’s gaze and slump back into a seat in their cubicle – not out of leisure, but exhaustion

from this performed exoticism.

“All that is seen as ‘performance’ in the art world is something that we ourselves grew up with,”

Muholi has stated. Somnyama Ngonyama, the ongoing self-portraiture series the artist began in 2012,

refuses the exoticising gaze. Whether using toothpaste mixed with Vaseline as lipstick or an assembly

line of clothing pegs to form a headpiece, Somnyama Ngonyama utilises elements of performance

with the immediacy of both political protest and African informal trade and craft markets.

The guerrilla nature with which these images are composed reveals the urgency to document the self:

“Portraiture is my daily prayer,” Muholi says. Their hairstyles, costumes and sets are entirely self-

realised, photographed with only natural light. Nomadic and impromptu, these shoots often take place

alone. This ‘African ingenuity’ so adored by the West without understanding, is rooted in necessity.

Muholi’s need is their manifesto for visibility: “This is no longer about me; it is about every female

body that ever existed in my family. That never imagined that these dreams were possible.”

Muholi’s three-dimensional expansion into bronze honours this familial origin, along with

commemorating Black women and LGBTQI+ individuals’ contributions to art, politics, medical

sciences, and culture. One sculpture depicts Muholi as a mythical being emerging from a body of

water carrying a vessel embellished with breasts upon their head. Another depicts a large-scale uterus,

which the artist describes as a “self-portrait of being”. Muholi invites the viewer to reconsider the

womb as a symbol of honour, protection, growth and non-prescriptive femininity: “The uterus is my

signature, it is my DNA, where I come from,” referring to a tattoo of the uterus on their upper arm,

imprinted in 2008. To raise the uterus as a deified form is to give honour where shame, violence, and

misinformation has plagued the organ for centuries.”

Speaking about the exhibition, curatorial advisor Beathur Mgoza Baker notes that it “interrogates

social, political and biomedical practices and conditioning that has placed women, girls, and non-

binary female bodies in conflict with their physical bodies. Central to their exploration is re-focussing

women and audiences generally around the importance of their reproductive and sexual rights and

autonomy.”

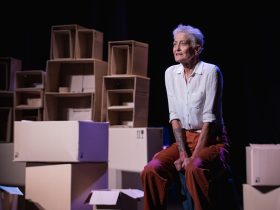

A two-metre high sculpture depicts Muholi sheathed in robes, their hands clasped in prayer, a restaged

Virgin Mary. The work connects to the sorrows of Mary as mother and protector, who endured

suffering by way of earthly sins. The work confronts the failure of law, religion, and politics to

adequately address gender injustice, directly referencing the artist’s Roman Catholic upbringing. In

prayer, Muholi calls for communal healing, remembrance and the resurrection of empathic conscience

and consciousness.

Confronting Muholi’s Black Madonna is a monumental bronze sculpture depicting the clitoris’ full

anatomy – the glans, body, crura, bulbs and root. Unlike the penis, which is sprawled on public

property from a young boy’s adolescence, the clitoris has been sanctioned as a taboo subject despite

being understood by women and female bodies as the center of sensuality and sexual climax for

centuries.

This transcension from pain into pleasure and from taboo to deity is Muholi’s creative mode of

survival – a revolutionary act explored in a large-scale bronze depicting the artist as a monk-like

figure. Wearing a trailing vestment and seated with their legs splayed and head tilted backwards in

ecstasy, this monastic figure performs the act of self-pleasure.

This euphoric release is further reflected in Muholi’s whimsical Amanzi (Water) photographic series,

which documents the artist submerging in a tidal pool. What begins in contemplative stillness, ends in

energetic dynamism as the waves combust around the dancing figure.

The freedom implicit in the Amanzi series is joltingly at odds with another large-scale bronze

sculpture that depicts a monstrous engulfment of the artist’s body, or rather their biologically

determined “box” – a term the artist uses to refer to the space encompassing their breasts and vagina.

In this queer avatar, Muholi’s figure appears trapped by malignant tubing that forms a strange,

amorphous mass around them – a reference both to the artist’s struggle with fibroids and gender

dysphoria. The piece is a poignant reminder of the somatic unease, anxiety and depression which

results from incongruence with one’s body.

ZANELE MUHOLI portrays the agony and ecstasy of existing in a Black, queer female body, and the

powerful nature of Muholi’s traverse through the world as both an artist and visual activist.

Leave a Reply