South African patients often find it difficult to access high-value, innovative medicines affordably. Addressing this inequity in access challenge may dramatically extend and enhance the lives of cancer patients. Reform of the current medicines pricing regulatory framework would enable the implementation of innovative access models to address the affordability challenges facing many patients.

The country’s increase in cancer incidence is predicted to rise from about 80 000 cases per year to more than double this by 2030.1a Reaping the benefits of affordable immunotherapy, for example, will require urgent legislative reform. The local cancer incidence in South Africa is the reverse of the United States where the risk of dying from cancer has fallen by nearly a third in three decades,2a thanks to earlier diagnoses, better treatments and fewer smokers, an analysis shows.

Treating cancer appropriately in will entail drastically improved access, investment in specialised equipment, procurement of necessary medicines, training skilled and specialist health workers and ensuring functional health systems to prevent secondary prolonged effects and side effects of treatment and disease. Added to these needs are vastly improved capacity for early diagnosis and treatment, and support for survivorship and palliative care. It’s projected that an additional R50 billion will be needed for cancer care by 2030.1b

Up to 20% of patients, (those with the correct bio markers), benefit from immunotherapy,3a a novel approach that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancers, particularly in ubiquitous lung cancer and melanomas. Other therapies, like traditional chemotherapies, also often work better in conjunction with immunotherapy, which may result in fewer side effects because treatment targets the immune system and does not affect all the cells in the body6. For example, an immunotherapy drug has been shown to treat Merkel cell carcinoma4, a rare but aggressive form of skin cancer, more effectively and with better survival rates than conventional chemotherapy – at present only few patients with this “orphan disease” have access to appropriate treatment.

The medicines Single Exit Price (SEP) regulation5a,b.c benefits patients on one hand, but denies an opportunity to explore innovative access models which would enable more patients to benefit from the latest oncology treatments. Although the intent of the law is good, it has the unintended consequence of preventing the implementation of innovative access models that would broaden access, especially to higher priced innovative therapies, and notably so when only a few patients suffer a particular disease.

Public sector hardest hit

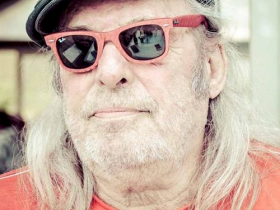

According to Dr Lydia Cairncross, Head of the Surgical Oncology Unit at UCT/Groote Schuur Academic Hospital, disparities between urban-rural and provinces in the public sector continue to disadvantage marginalised communities1c, particularly in accessing specialised cancer care.

“Media reports regularly highlight desperate patient appeals to funders, government and patient groups for financial help to enable continued treatment, particularly around access to innovative therapies,” says Dr Cairncross. “The tragic reality is that too often an oncology diagnosis, even among those with access to private insurance, can result in ‘financial toxicity,’ and too often, death. This is mainly due to co-payments being unavoidably levied on patients, putting the most effective, (and so far, unavoidably expensive), treatments out of reach for most. Timely access to such therapies can be the difference between life or death.”

According to Dr Ronwyn van Eeden, a medical oncologist working in Rosebank Clinic and an honorary consultant at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, “SEP and high prices of drugs make it difficult for most patients to gain access to innovative drugs. We need to have discussions about bringing new therapies in a more affordable way to patients in both the public and private sectors (as only 10% have access in private and almost none in the public sector). There is also a need to find alternative ways to support the hefty co-payments patients are faced with in private.”

Unintended consequences

Dr Jacques Snyman of Agility Health concedes that private sector transparent medicines pricing regulations, the SEP, and regulated dispensing fees are intended to make medicine prices transparent and manage inflation-associated price increases. However, he emphasises, these pricing mechanisms have hindered the ability other countries have, to agree on specific access conditions for

innovative medicines where costs are not covered, or covered only partially, by an insurance product or medical scheme benefit. “This is especially true of high-value innovative medicines where much more is required to enable affordable access to life extending and life enhancing treatments,” he says.

According to Dr Snyman, the SEP prevents access to programs for patients in both sectors and contributes to out-of-pocket payments for medical aid members. “Governments and health care systems around the world are realising that having a single transparent list price for a drug is not the best way to provide affordable access to all patients who can benefit from a treatment. Differential discounts, blended prices that reflect different values for different indications, outcome-based pricing, and subscription models are amongst the innovative models now being used to increase access whilst promoting value for money and affordability,” he says. “Some require data collection and monitoring, but often proxy measures can be used to keep administration costs down.”

Dr Cairncross illustrated ubiquitous delivery bottlenecks that also contribute to inequitable access: “Of the 200 radiation oncologists in South Africa only 44 are employed in the state sector, a shocking indicator of the disparities in the capacity to deliver cancer care. This disparity extends to other health care workers such as nurses, pharmacists, radiographers, physiotherapists, lymphoedema specialists and palliative care nurses. Even within the private sector, patients receive different standards of care depending on the specific medical scheme option package they can afford. Many are subjected to crippling co-payments to complete their treatment.”

Dr Omondi Ogude, a Sandton-based medical oncologist, says Covid-19 has already stretched and tested, and in some areas nearly collapsed, parts of the South African health system, adding to general healthcare access woes. “This makes finding cost-effective solutions to enable life-saving treatment all the more important. In the fast-progressing world of medicine, it has become imperative to find the right treatment for the right patient – at the right time,” he says. “Other priorities include ensuring optimal duration of treatment that will provide the best possible clinical outcome for the patient and reduced wastage for the payer.”

The four experts agree that innovative treatment usually comes at a high price due to the cost of drug development but should be accessible at a cost that is affordable to both the patient and the payer. Payers should be able to provide life-saving treatments to their members within manageable risk limits and with a sustainable budget impact. Any feasible model must also address affordability and willingness-to-pay constraints that hamper patient access to care and must be legally compliant.

Leave a Reply